Speech by Jerry Kay, grandson of Karl Kutschera, on the occasion of the installation of a memorial plaque at Kurfürstendamm 26 on 22 February 2018

Why are we coming here today, and what do we commemorate with this Gedenktafel (Memorial Plaque)? For me the answer is easy. This building was the place where my grandfather, Karl Kutschera built what he called ‚his life’s work’ from 1919 until he died in 1950. My Stiefgrossmutter, Josephine Kutschera Hildebrandt carried it on until the early 1970’s. My father managed the business before emigrating to America in 1938. I first came here in 1950 when I was three years old.

But what exactly was Karl Kutschera’s life’s work?

He grew up in a small farm village of Upper Hungary, now Slovakia. His parents owned an inn and farmland. As a young boy, Karl fell in love with the atmosphere in the inn, where townspeople and guests gathered. He saw a kind of magic happened when people came together over coffee, food and drink. They became happy. They became joyful. Sometimes they even became creative.

So at 13 he moved to Vienna, the capital of coffee house culture to learn the business. He worked in cafés where writers, composers, artists and intellectuals sat with their coffee and wrote books, theater plays, newspaper columns or essays; they composed music, sketched pictures or ideas for buildings. They dreamed up new inventions or scientific concepts. And when they gathered around their Stammtisches (Regular Tables), they not only made jokes and gemütlich (genial) camaraderie, they discussed, debated and collaborated. My grandfather understood that this vital European institution could be a public place to inspire and advance civilization.

When he came to Berlin in 1900, Karl Kutschera wanted that kind of café, along with other famous Berlin cafés, the Romanisch, the Café Des Westens, — a place in the middle of the city where people with great minds and talents could come and escape the noise and clutter and clatter of the big city and be able to open up their minds and spirits and souls to contemplate new art and literature, new music and fashion, new inventions, new ideas.

And then, a few years after the destruction, humiliation and chaos of the First World War, suddenly militaristic, stodgy Berlin flowers in the Golden Twenties into a Weltstadt and anybody who wants to be on the cutting edge has to come to Berlin.

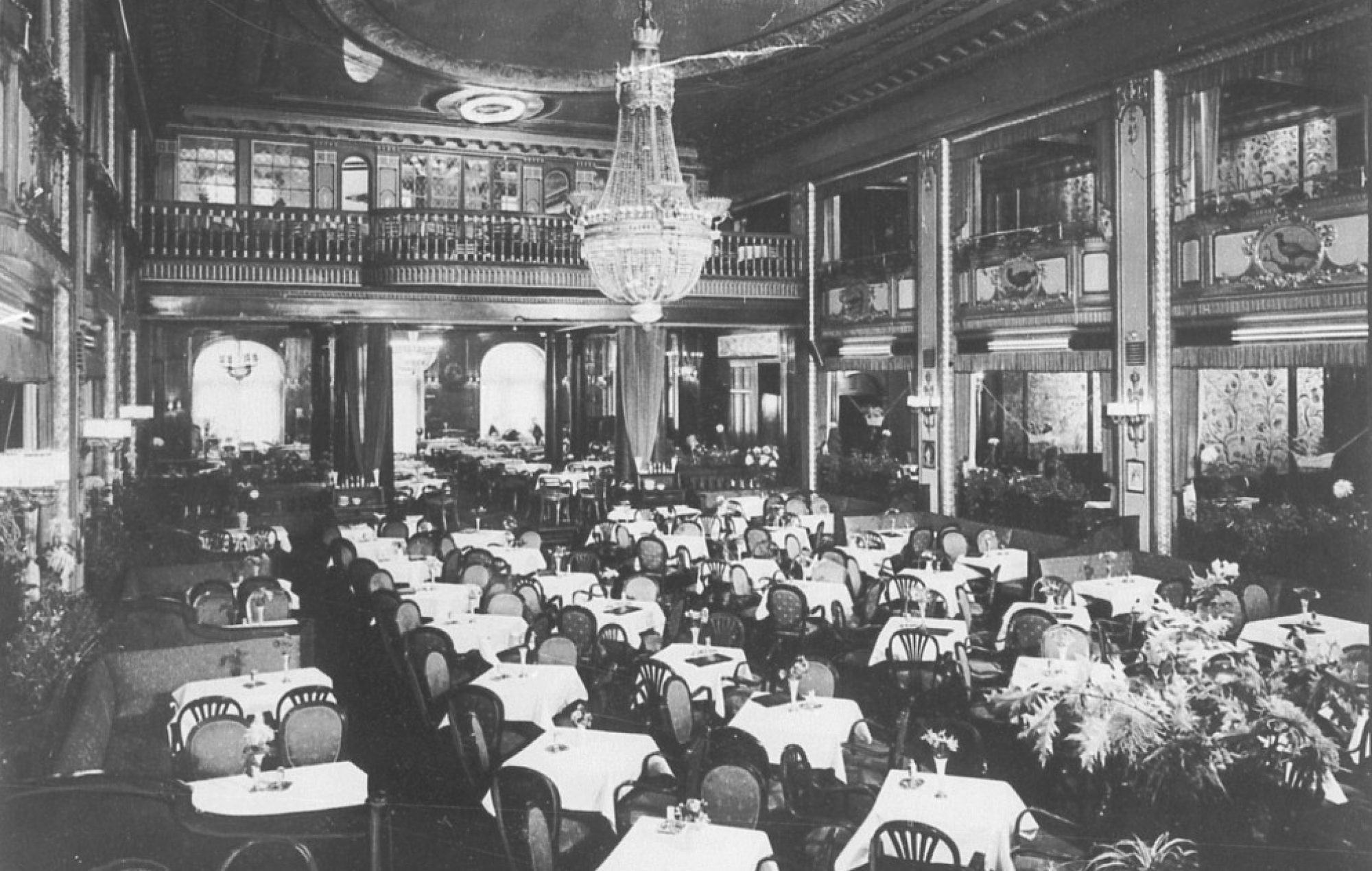

And, yes, they came. In the chairs and around the tables in Café Wien, sat famous playwrights, journalists, cabaret, theater and film producers and directors and actors and actresses. Often they met at a large round table, their Stammtisch in the back and one of the things they did was pay for fifty up and coming artists and writers a day of their choice to come and dine at Café Wien. It wasn’t until after Karl Kutschera died that one of the group confessed that the idea was Mr. Kutschera’s who paid for it, but swore them all to secrecy. Kutschera wanted it known as their gift.

Up in the billiard room, a young film writer, Billy Wilder came with his director friend Robert Siodmak thinking up scenes for his first credited film, Menschem Am Sonntag (People On Sunday) – which premiered in the adjoining movie theater in 1929. Dancer Josephine Baker showed up one evening in a group that included theater producer Max Rheinhardt. Boxing champion Max Schmeling entertained his Jewish friends often downstairs in the Zigeunerkeller– before helping them escape to freedom.

Albert Einstein sat in Café Wien conversing with world chess master and philosopher, Emanuel Lasker. Another Einstein friend and collaborator, Leo Szilard who had designed the first electron microscope tried to persuade inventor, Dennis Gabor, the father of holography in Café Wien to build it in 1928. Unfortunately, German civilization was not solid enough to withstand the forces that led to National Socialism, and Karl Kutschera and most of his family who had not left Germany, lost everything and were sent to Concentration Camps. His two youngest children, his brothers and sisters, aunts and uncles, cousins, his colleagues perished. But Karl and his wife, Josephine survived and returned to Berlin, and Café Wien was returned to him.

What was he to do? Leave Berlin, sell the café and settle with surviving family in other countries? No, he chose to stay in Berlin. He chose to believe that as horrible as Germany had become, there still burned in some of the people a light of civilization he had always worked to build in Berlin. His older son, my father who had left for America did not agree with him. But Karl persisted and through the tough years after the war maintained Café Wien as a symbol of what Berlin had been and still could be again. When he died in 1950, my Stiefgrossmutter (Step-grandmother), Josephine kept it going and then married Paul Hildebrandt; and together they helped create and host in their Film Bühne Wien and Café Wien the Berlin Film Festival which brought the city international cultural stature once again.

This is why this building is so important, not because of the celebrities, but because Karl Kutschera dedicated himself to making Café Wien a place where people over a cup of coffee and a strudel, could ultimately contemplate how to make society better or at least, more enjoyable.

I want to thank everyone who helped to make this day possible. Jerry Kay

Jerry Key’s speech on YouTube